- A very low-calorie diet has been shown to help patients with diabetes control their blood sugar, according to new research from the University of Pittsburg Medical.

- After 6 months, 12% of participants were in remission, meaning they could manage their blood sugar without medication.

- This diet was particularly helpful for patients who lost the most weight, the researchers found. A follow-up study is planned to determine the long-term effectiveness of the program.

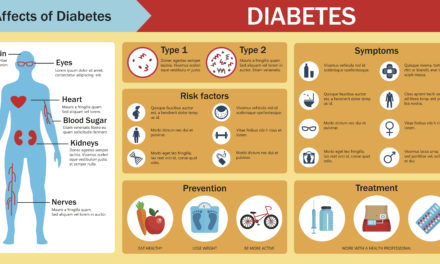

A low-calorie diet may help patients with diabetes control their blood sugar without medication, and even reach remission, according to new research presented at the virtual Obesity Week conference November 2 to November 6.

Strictly reducing calories may work to help diabetes patients by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing stress on the pancreas, the organ that produces insulin, according to Evan Keller, a medical student at the University of Pittsburgh who led the research.

The study tracked data from 88 patients with diabetes who successfully completed the university’s weight loss program. Patients consumed 600-800 calories a day for three months, in the form of high-protein meal replacement shakes. They then gradually reintroduced other foods, while maintaining a calorie deficit and avoiding foods that spike blood sugar, such as processed or sweetened foods.

By the end of the program, 12% of the patients had their diabetes in full remission, meaning they were able to control their blood sugar without using any medications. Another 11% of patients were in partial remission and were able to use less medication.

“We found the program is effective at achieving diabetes control on or off medication,” Keller said in the presentation.

Patients who lost the most weight saw the greatest benefits for their blood sugar control, he added. On average, patients lost 17.3% of their starting body weight by the end of the program. But patients in the highest weight loss group had significantly more improvements in blood sugar control than patients who the least amount of weight.

Keller said these results are promising, but the next stage of the research aims to follow up with the patients for a 12-month period after the diet program to assess its effectiveness over time.

“People want to see the long-term data and see if this diabetes remission is really sustaining itself,” he said.

Previous evidence shows fasting can help control diabetes by restricting calories, even without weight loss. Previous studies suggesting that limiting calorie intake through fasting can also help diabetics manage insulin sensitivity and blood sugar.

In a study, a 57-year-old woman was successfully able to manage her diabetes without medication through a combination of fasting, calorie restriction, and a ketogenic diet.

The patient in this study consumed 1,500 calories a day, four days a week, and fasted regularly, sometimes for 42 hours at a time.

Four weeks into the diet, the patient was able to stop taking medications such as metformim, an antihypertensive and a statin, while still being able to control her blood sugar levels.

Four months into the program, her blood sugar levels had significantly improved, even without the medications.

Extreme calorie restriction should only be done with professional supervision.

While these results are promising, diets that severely limit calories for an extended among of time can be risky. Severe calorie restriction can lead to muscle loss and fatigue, along with feeling of cold, hungry and irritable.

In extreme cases, it can even lead to serious health consequences, such as irregular heartbeat, dizziness, dangerously low blood pressure, and even unconsciousness, which can potentially cause injury or death. Intensive calorie restriction can also be harmful for people with a history of disordered eating.

As a result, anyone interested in trying a very low-calorie diet should consult a medical professional, and routinely follow up to make sure the diet is done as safely as possible.

Image Credit: alvarez; istock